Threefold, triads, and triskeles...

The number three seems to be the one important number in Celtic folklore

- Triquetra

- Golden “Triquetra” or “Trinity Knot”

- Credits https://irelandtravelguides.com/trinity-knot-triquetra-history/

- JPEG - 97.9 KiB

Although it is not yet proven why, several theories have been made about the possible symbolism of this number. In his Dictionary of Celtic Mythology, James MacKillop gives a number of symbols and elements that can be represented by the number three, the most striking ones being time as past, present and future; “the visible world” as sky earth, and underground; and life with male, female and progeny [1] or possibly male, female, and what has been named in modern times non-binary, which was already present in prehistorical times as, for instance, in the figure of Loki which is more and more studied as a gender-fluid or even genderless mythological figure.

Putting genders aside, the number three in Celtic societies has been shown to be the most present in folklore, especially studied through the lens of the tripartite division of Indo-European societies with the three classes being defined by Dumézil as such:

la souveraineté avec ses aspects magique et juridique et une sorte d’expression maximale du sacré; la force physique et la vaillance dont la manifestation la plus voyante est la guerre victorieuse; la fécondité et la prospérité

Dumézil’s theory was mostly accepted as a general organization of Indo-European societies, although it has been argued that these societies did not consciously organize themselves in such a way, if they did at all.

The tripartite function has also been applied to the triple death motif two bog bodies from the British Isle

Lindow Man and OldCroghan Man have both undergone a triple death by cutting, hanging, and drowning.

-

Lindow Man, also called Lindow II, was found in the Lindow Commons near Wilmslow, Chesire. Excavated in 1984 in the peat bog, he was identified as a young man, of seemingly high status, dated between 2BC and 119AD.

-

- Lindow Man

- Upper half of human male body, aged approximately 25 years at death. Found preserved in a bog. Hair and skin well-preserved. Remains of a fur armband around left arm and a garott of animal sinew around neck.

- Credits © The Trustees of the British Museum

- PNG - 215.8 KiB

-

-

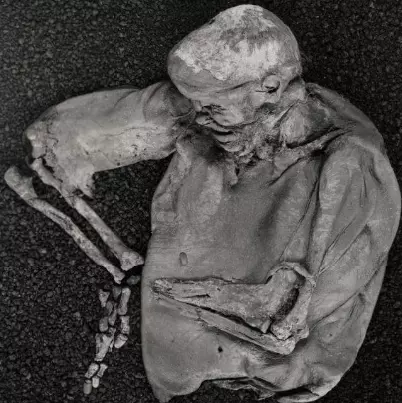

Old Croghan Man, was found in 2003 in Ireland, in the peat bog at the foot of Croghan Hill, County Offaly, near the border with County Kildare. Also a young man, and thought to have been of high status as well, he was dated to have died between 361BC and 175BC.

- Old Croghan Man’s Hand

- Detail of Old Croghan Man’s hand

- Credits National Museum of Ireland

- JPEG - 104.2 KiB

Both bodies, thus from the Iron Age – or potentially close to this period for Lindow Man – are victims of a triple death, although with some differences, share a high status, and were both young male adults, apparently around twenty years old at the time they were killed.

The violent threefold death of kings

- Medieval manuscript

- Picture of a medieval gothic manuscript with a gold-illumniated “T”

- Credits Henryk Niestrój

- JPEG - 158.5 KiB

The violent threefold death of kings is also to be found in the Irish Cycle of the Kings: in Aided Muirchertaig meic Erca, found in several manuscripts from the 12th to the 14th century; in Aided Diarmaita meic Cerbail, in the Life of Saint Columba. But this threefold death motif is also to be found in Insular Celtic wildman tales such as Buile Suibhne (the Frenzy of Suibhne); and can also be found in Geoffrey of Monmouth’s Vita Merlini, and in two Latin texts about the figure of Lailoken, found in a 5th-century manuscript: Lailoken and Kentigern, and Lailoken and Meldred.

The sagas and the hagiographies share the motif of the triple death, which Lawrence Eson summarized as such, based on Joan Radner’s article “The Significance of the Threefold Death in Celtic Tradition”: “the future victim commits an offence; there is immediately a prophecy, almost always delivered by a cleric, that the offender will be punished for his offence by a threefold death; disbelief in the prophecy is expressed; the events of the story bring about a reversal, and belief may be explicitly expressed; the prophecy is fulfilled and the offender/victim is killed” (Eson, 2010).

This summary applies to the sagas quite perfectly, which depicts the offence done by the kings Muirchertag and Diarmait, who are then punished by a threefold death.

But, nuance is to be brought in the study of the hagiographies, the Vita Merlini, and the texts about Lailoken.

-

- Merlin

- Merlin in Robert de Boron’s story

- Credits BnF

- JPEG - 36.2 KiB

- In the hagiographies and the Latin texts about Lailoken, the saint or wild man prophecies their own threefold death, and not the death of another for a particular offence.

- In the Vita Merlini, after revealing the adultery of the Queen to the King, Merlin is asked, by his sister the Queen, to prophecy the death of a young boy at three different times, and prophecies three different deaths for the boy. Merlin is thus thought to be unreliable, and the Queen’s adultery is believed to be an invention of the madman. The boy later dies a threefold death, and his prophecies are thus believed. The motif of the threefold death can thus somewhat differ from one tale to another.

The motif of the threefold death, or triple death, can thus be found in several literary narratives, the sources of which are mostly impossible to date, besides being found in the analysis of the Iron Age bog bodies Lindow Man and OldCroghan Man.

Why a comparative study of literature and archaeology?

A comparative study of the literary sources and the archaeological findings could, possibly, bring some light to the context in which such narratives may have emerged, or on the context in which the bog bodies have been killed. such a study should not pretend to be able to affirm a dating to the literary narrative, nor to assimilate the bog bodies as an explanation, or source for those narratives. But comparing the two could shed some light on the motif of the threefold death and how it occurred in the Celtic societies.

Notes

[1] (MacKillop, 1998)